Most of the group headed out this morning for a cenote visit. The Yucat?n Peninsula is pretty much devoid of rivers and streams. In Mayan times the only fresh water to be found was in the natural limestone reservoirs that occur in their thousands in the area, the cenote. We would be swimming in some of these underground pools.

With eleven of us booked we had our own private van and driver. The trip out of M?rida took us west in the general direction of Chich?n Itz? along the main road. Diverting we took a series of smaller roads through a couple of tiny rural townships before pulling up at a rundown collection of roadside buildings. I don’t know the name of the place; I’ll have to update this text later. We parked off the road near a tree under which I took cover from the fiery blast of the sun. There were some local men lounging about on what looked to be funny wooden seats. These turned out to be the buggy’s we would be pulled along in by the horses that started to appear out of neighbouring properties. The tour would have us in groups of four pulled by horse power along narrow rails, stopping at three different cenote to have a swim.

Our horse and one of the buggies

Keryn and I were in a buggy with Ben and Lisa. The bumpy ride to the first cenote seemed to take an age, thankfully we has a cloth roof over our heads to shield us from the sun. We clattered and rattled for about fifteen minutes until we got to the signposted path of the first sinkhole. The drivers took the buggies off the tracks and led the horses to shade, waiting while we took our dip. We were led to a hole in the ground with a steep staircase heading down into the gloom. Heading down the sun came out from behind a cloud and the water below turned a rich sapphire blue. We reached a platform to look out over a large pool of clear blue water, the colour deepening as the light faded further into the cavern.

Experimenting with the camera in the first cenote

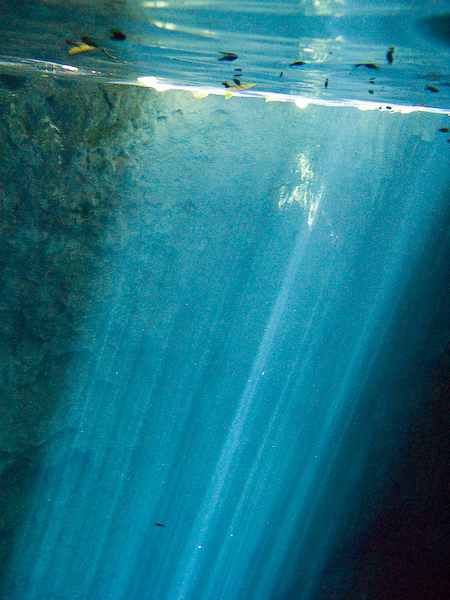

Sunlight streaming through the water

People either dived in or took the more sedate route of stairs that went down to the waters edge. The water was cool but not too cold, almost the perfect temperature really. We could see the occasional small black fish and after a while bats were spotted flying from hidden crevice to dark hole in the back of the cavern. This was the first chance Keryn had had to try out the underwater housing for her camera and it worked well. We experimented with photos, trying to get shots that contained combined underwater and surface together to limited results, much more practice needed. In all we spent about half an hour in each of the cenotes, with a bone jarring ride separating the blissful submersions.

This is what someone diving in to the pool looks like from underwater with a slow shutter speed. In this case this is Mark.

The second cenote was more of an egg shape with a narrow hole high above the centre of the circular pool. There was less light here but a large tree had pierced through the ceiling and its roots came down all the way to the water level, twisted together into knotted ropes that could be grabbed by those swimming. Occasionally shafts of light would appear from small crevices in the limestone roof, illuminating the water with shimmering beams. The platform here was higher and there was some creative diving taking place. Up top by the entrance a sign warned people to not dive in from the ground level. We were told by our guide that once a woman had tried this long dive and had broken her back, in so much pain she wouldn’t allow anyone to touch her. The woman had to be manually carried out of the cenote and transported to the road on a horse drawn buggy – surely a process that would have crippled her for life.

The final cenote was the most difficult to access, a narrow opening allowing entrance only by means of a large wooden ladder. The platform at the bottom of the ladder could only be seen once the climber was two thirds of the way down, this wasn’t access for anyone not confident in heights and the unknown darkness. Once at the platform we could again either jump in, climbing the platform barrier, or walk to the water level on wide steps. There was another tree dangling its roots to the water and more bats. A pile of rubble in the middle of the pool came to a point under the roots, obviously where part of the ceiling had collapsed. Larger fish could be seen calmly moving through the water, only to disappear as the people entered.

The final cenot?

Mark and I were the last to leave and we stood on the bottom step taking photos as the water got smoother and was finally still. The fish seen earlier started coming back to the surface and the bats were flitting in circles near the ceiling, making occasional bat chatter. We briefly discussed how natural places like this, especially these cenot? that seem to be mostly untouched (other than the man made steps and ladders for access) are ultimately more impressive than any monument or building. Maybe seeing all these ruins, all these different made places on our travels, gets a bit too familiar in the end. Man came, he built, he moved on. Possibly any apathy on my part relates to the book I’m reading at the moment; The Wild Places by Robert Macfarlane. In the book Robert is searching for the remaining wild places of Britain, those spots that form remnants of ancient woodland or other wild landscape largely untouched by the hand of man. Reading of nights spent on old moors, next to isolated lochs or on the top of mountains sounds much more adventurous than our air-conditioned bus travel from one tourist spot to the next. I hope we see more of nature on our trip than we have so far. Being by the ocean will help with snorkelling opportunities or in Keryn’s case diving.

It was a pity to leave the cenot? but as least we’d had the time mostly to ourselves, with only a few other small groups of people arriving at each place. On the return journey we met other groups and buggy’s had to be taken off the single track to allow one group or the other to pass. We were driven back to M?rida and the group dispersed. Keryn and I got our washing and then rested. I got up at one point to find out what was happening outside, it sounded like a parade. Finally catching up with the noise at the Z?calo I watched a protest march accompanied by loud music parading around the square before heading into a building. With Ben and Lisa I went to the nearby supermarket in the early evening and we bought some cold beer to share with the group during the evening catch-up. Juan Pablo explained the next days travel arrangements and then most of us went out for dinner at a cheap but cheerful restaurant near the centre of town. It wasn’t a place we would normally have picked, looking both run down and dodgy, but the food was in generous portions and was also well priced (read cheap) and tasty. Juan Pablo ordered some extra hot peppers which went nicely with my pizza. Then it was back to the hotel for us two tired kiwis to pack and try to sleep in the stuffy, humid room.

Some of the people marching around the Z?calo

Just found which Cenote we visited:

Cuzam?. Three spectacular cenotes are located near the village of Cuzam?. They can be reached by hiring a guide from the village. The guide carries equipment to the site via a horse-drawn cart running over an abandoned narrow gauge railroad. The entrance to Bolonchoojol is a hole in the ground with a ladder constructed by welding old railroad ties. Inside is well-lit cavern with crystal clear water and huge stalactites and stalagmites. Chansinic’che is another cenote at Cuzam?, also accessible with a railroad tie ladder, but a faster way to enter is to dive from a precipice near the surface (about 10 meters). Chelentun is much more open, and can be reached by a concrete staircase built into the rock, with a handrail. The entire cave is swimable.